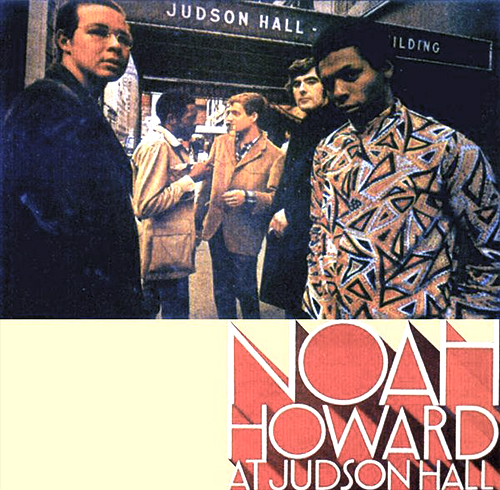

Tracks

- This place called earth

- Homage to Coltrane

About the album

All compositions by Noah Howard.

Recording: 1966

Label: ESP

Recorded with

Dave Burrell

Rik Colbeck

Norris Jones [aka Sirone]

Bobby Kapp

Catherine Norris

Notes by Lionel H. Mitchell

Lionel H Mitchell is an award-winning Afro-American writer and a very close childhood friend from New Orleans. In 1981 Lionel H Mitchell won the American Literary award for his novel Traveling Light.

A few short years ago (when according to the prevalent academic dogma—”the Negro was the only group in America without a culture of its own”) black expression took place in an almost hopeless situation-white critics wrote out of a peculiar arrogance—they had the word, the media, the oracular vision as to what would or would not capture the fancy of the marketplace and when they came to perform their God-role on the work of an artist it was to marshall a closed cycle of profane functions against him. Because they were so over-entrenched criticism came to resemble a fait accompli. Argument, opposition was useless because the artist was lead to feel that the very tools he used could be given or taken away by a priesthood of commentators. In the late fifties when jazz criticism became the near private fief of blond jazz-bucks in search of a new male principle; the level of neurotic content in print on the subject became almost unbearable and the fountainhead of Black American creativity seemed to exist in a near feudal situation… but not quite, because there.was no-real nobility (or rather those who assigned themselves the role seemed like “draftees from a Conrad novel… adventurers smack out of Cape Colony days, goldrushers clothed now in liberalism and alienation.) The revolt came out into the open in due time but the counter-revolution has not been worsted as yet…witness the educational charm in the statement of a hippie who told this writer: “Spade music is monotonous.” Out of great humanism, this writer suggested by way of therapy that it is neurotic (may be even psychotic) to count one, two, three, four along with a James Brown or Otis Redding…Black music exploded in the face of its levi and leather lords and when the smoke cleared, the assault centered around esthetics. It became obvious that when the artist and his critic used the concept “beauty” they meant quite different and often contradictory things.

Existential situation, point-of-view figured along with basic experience in this war—a gap that can no longer be spanned by the usual tools of the critic (namely bad faith, bad poetry and cultural piracy!) Today the European critic, with a stronger tradition of good taste (not to mention a greater respect for its limits) manages to avoid some of the self-annihilation of his American novice by the fact that he does not share in the latter’s sense of cultural insecurity and feels more relaxed about what Janheinz Jahn has called “neo African culture.” Black musicians find, for instance, that abroad their music is dealt with in a fashion that is considerably more straightforward than the Americano variety. The European capacity for charm, however, must be kept in its historical context or, as Fanon has put it: “Europe now lives at such a mad, reckless pace that she is running headlong into the abyss; we would do well to keep away from it.” Any compilation of the primary ideas of that culture would suiFice to demonstrate this contention but for our purposes here the following list will suffice: the ferocious superstition that the sacred and the sensual are antagonistic; the notion common to both Europe and the United States that the whole of humanity must worship by default this new nuclear diety which is the image, graven and exclusinve,of human selfdestuction entailing as a logical sequence an esthete of dying,the imperialism of death !

Indirectly therefore, we have approached the thematic raison d’être of Noah Howard’s composition, THIS PLACE CALLED EARTH. Conceived and partly written in flight, it is a series of paradoxes, ironies and contradiction even, revealing themselves only through total listening because the music is no longer one music or a music. It is about total-like sound surging into many or all dimensions and introducing the listener to total freedom (which for some may serve to rudely reveal limitations−the detour signposts of being) so therefore strict historiography is an inadequacy of the tools and not necessarily a gap in the art. A ‘long meter’ or dirge or wail is stated early in the work and proceeds in the form of the sacred hymn of the Southern Negro Fundamentalist churches into the fury of the music and outlives that fury. This theme can be taken as a homage to the mainstream of black creativity in the United States because hymns as such as; “I love the Lord, he heard me cry!” are African Chorals to which Christian lyrics were attached much after the Middle Passage when it became legal to teach the slaves the religion of Christ. Mr. Howard, practically acting out the history and development of this music with his own instrument, stretches the theme until at times it becomes like the funeral marches of the Young Tuxedo Brass Bands of his native New Orleans, includes the triumphant jump back from the brother’s grave with the wine bottles glinting in the sun outside St. Louis Cemetery and at the highpoints of his ecstasy he reaches the blues. It must be recognized, however, that this dirge is in a sense incidental because the overall form of the work sets it in the jet age and is therefore designed within the symbolism of the steel bird−gunning the engines, taking off, soaring into the blue, rocketing beyond the speed of sound to a ringside seat of the universe. In the discussion, which takes place none of the instruments have what can, strictly speaking, be called, a supportive role−they are all individuals seemingly going their separate ways…

In other words, the quality of this music must be sought within what Leopold Sedar Senghor terms “…a mathematical formula founded on unity in diversity.” Not only does each instrument carry its own line of rhythm but also there no longer exists any rule requiring strict vertical relationships between these rhythmic lines (which are progressive, provocative, sometimes entwined criss-cross and mutually catalytic.) It is an easily recognizable feature of the post-jazz era that each composer constructs his work out of a battery of idioms taken from music in the totality of time, thus the concept of “new music” is banal. Also the solo medley is now interwoven with percussive responsibilities or, as the major composer-theoretician; Cecil Taylor has put it: “The paths of harmonic and melodic light, give architecture sound structures acts creating flight”

Possibility in music is once more introduced to the infinite characteristic of the universe−symbolized by the creative imagination pushing towards unity with the cosmos whether through what used to be called “by ear” among old-jazz musicians. In terms of history, the only comparable European music is the Baroque but there diversity was limited to one or two dimensions and the dynamics were inordinate and freedom unknown. Moreover, the present day notion that serious music cannot be danced-to is in for destruction, as witness Mr. Howard’s HOMAGE TO COLTRANE.

For the musician and the poet, silence and sound have equal importance−a two-backed beast of conception. Rhythm relates to silence rather as the hand does to a glove. When Billy Holliday sang, for instance, she implied an incidental infinity of songs. What has already been said with regards to THIS PLACE CALLED EARTH should become more obvious and clear in HOMAGE TO COLTRANE with the exception that the composer has introduced his idea to us in the first work, it may not be clear to us what he wants to do with that idea. On side B, however, he reveals his transcendental intentions (which seem to entail honesty to Western contributions in music while at the same time moving towards the East.) Thus, you have the continuum of the Progressive era with its propensity to experiment with “symphonic” instruments, demanding hitherto unknown versatility from them towards the aim of producing new sounds (note the raga production from bass and cello.) Moreover, any homage to Coltrane will henceforth be required to use the form of “preacher’s rhythm” because its restoration to music during a time when it was abandoned in literature (under the onslaught of anti-Baldwin criticism … i.e. Baldwin’s “preachiness”.) must be listened among greatest achievement of John Coltrane.

Naturally, any commentary upon the work of an artist must of necessity be skeletal in character, only the listener can complete with the aid of his “receiving” devices what began with the artist; hence, the main function of comment is to indicate…In addition to what has already been said, listeners familiar with Mr. Howard’s earlier work will notice a new level in tone quality from his alto and more vigorous individuality and self-expression on the part of all the instruments… It is such a pity Black artists in the United States do not develop (or at least that is the impression to be had from the magazine culture) they simply occur and it must be added that the cultural identity discussed here follows its age-old principle of remaining flexible and allowing fresh, free expression to all those who associate with it.